By Idowu-Fearon (PhD)

It is a great honour to be here on this most significant day for our graduates, and indeed for all of us who gather here today. We are here to celebrate and affirm what you – our graduates – have achieved through your studies, and to encourage you to take forward what you have learned so that each and everyone of you might play a role in bringing about positive transformational change for our beloved state of Kaduna, other Northern states, and our country. Not that I wish to place too much pressure on you on a day that is meant for celebration!

My theme today is ‘the role of education in peace building and peaceful coexistence in the Northern states of Nigeria’. Indeed, that is not only the theme of my remarks, but actually the theme and the purpose of this centre. Since its founding, this centre has been a house of peace (bayt -al-salaam) – perhaps we might even call it an oasis of peace (wahat-al-salaam) – in the midst of the many challenges that we face in this part of our country.

We see many weapons used here in this region – there is conflict, and the weapons that are used cause great harm, not only to individuals, but to families, to communities and to our society as a whole. But we have the tools and weapons of our own to push back against this violence, which is very often set up as a conflict between Christians and Muslims. Nelson Mandela famously said, “education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” And he was right. Education is the weapon that we must all be willing to use in our efforts to live in peaceful coexistence with one another. And that is why this institution is important, and why those of you who are graduating today have taken such an important decision in choosing to undertake your education in this place. We are honoured to have the Executive Governor of our state and esteemed representatives here with us today.

I would like to take this opportunity to address you directly. You can see here the value of investing in high-quality education and the positive impact that it can have on communities. What we have done here is recognise that there was a gap in high-quality religious education and that is one of the root causes of the issues we face in this part of our country. I would encourage you wholeheartedly to see how increasing government investment in religious education can be one pillar of a response to violence and to conflict. The key purpose of education is to open our minds to new thinking – to understanding the views of others. It is not simply to affirm what we already believe and think we know. This can be especially damaging when it comes to religious education – or a lack of religious education.

When we think we know all we need to about the religion of the ‘other’, – whether you are a Christian or Muslim – and are unwilling to expand your knowledge, there is a very real risk that you are yourself part of the problem, rather than being part of the solution. How can we ensure that our youth are continuously learning about the beliefs of those who are different from them? Through good religious education. This is something that can be championed by government, and supported by religious leaders and through institutions like Kaduna Centre for the Study of Christian-Muslim Relations. As I speak of religious leaders, and speak as a religious leader, I also acknowledge that we have a significant and weighty responsibility to practice what we preach when it comes to our understanding of our own religion and a good, working knowledge of the ‘other’ religion.

In my travels around the Anglican Communion as its Secretary-General, I am sometimes concerned to discover that religious leaders do not have an in-depth knowledge of what it means to be an Anglican. We are getting our own house in order through supporting our bishops in accompanying them in their role, and through more emphasis in theological education, which is something that we have invested in at our offices in London and in our colleges, seminaries and other institutions around the world. We must take a similar approach here in Nigeria and particularly in the Northern States.

Religious leaders need to be accountable to one another. We must be willing to challenge one another when we hear things that are false. This is particularly important when we speak about the ‘other’. Our congregations and our followers trust us. We have an obligation to them to speak the truth – and to actively ensure that we are speaking truth, by educating ourselves to a high enough standard. To be educated in this way does not mean that we must agree with everything that we learn. Not at all. There are many differences within and between religions that express a diversity of beliefs.

But we must be willing to hear what others believe, and to be able to grapple with these issues in a peaceful manner. And we must proactively find the opportunities to grapple and discuss. Ignorance and all that comes with it – fear, hatred, and conflict – happens because we separate ourselves from those that we disagree with and from the ‘other’. We might do this out of concern for ourselves – that if we are seen to be speaking with someone who is the ‘other’ that it will damage our reputation with our own communities. But this also happens because of fear and sometimes hatred. These are things that we must also work against.

And we must resist this temptation to separate ourselves from those who are different and with whom we disagree. Therefore, we must engage in activities together. It is not enough to simply have knowledge and understanding in your head. You must also practice what you learn. Religious leaders can set a good example in engaging in activities with leaders from the ‘other’ religion – perhaps sharing a platform on issues of mutual concern, or taking part in activities that build trust and relationships.

And these examples must be encouraged at all levels of our society, from the very top right down to activities for children in schools. I come back to the quote that I began with from Nelson Mandela: “education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” I strongly agree with this statement. But we also know that education is a lengthy and ongoing process. It does not happen overnight. It requires commitment. Investment. Sustainability. Cooperation. Another wise man said this about education: “Knowledge is power. Information is liberation. Education is the premise of progress, in every society, in every family.” Those are the words of Kofi Annan. I am struck by the phrase ‘education is the premise of progress’. That is what we need to focus on – progress. There is much to do, and education alone cannot solve our problems.

But where we see progress, we find encouragement. We have seen progress here in this centre. We have made much progress since it was founded 15 years ago. Many people have left this place transformed, committed to making progress and to being peace builders (bunat al-salaam) for our communities. Let us hope and pray that in another 15 years, the work of places of education like this centre is not unusual – that what is taught here is common in our schools, colleges and universities. That we all know much more about the ‘other’ and that we engage together much more. This graduation is a powerful image of progress and one that we can all be inspired by.

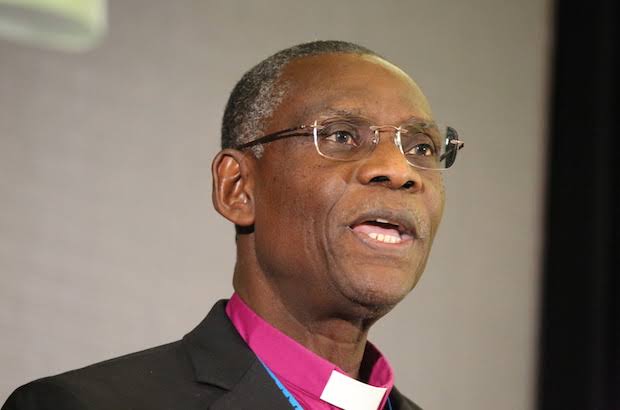

The Most Reverened Idowu-Fearon (PhD) is the Secretary-General of the Anglican Communion Archbishop Josiah Idowu-Fearon. He presented this paper at a graduation ceremony of the Kaduna Centre for the Study of Christian-Muslim Relations in Kaduna on Saturday.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Sky Daily