By Abdulbasit Kassim

As long as you are active on any social media platform, by now, you should have read, or someone must have shared the trending David Hundeyin’s article “Cornflakes for Jihad: The Boko Haram Origin Story” (https://westafricaweekly.substack.com/p/cornflakes-for-jihad-the-boko-haram) with you. Regardless of his political positions, David Hundeyin dug up the archive that most people in the religious establishment of northern Nigeria know but would instead prefer to be silent upon. Although David often raises interesting issues in his investigative articles, he can sometimes appear too sensational and quick in reaching conclusions.

Andrea Brigaglia, Alex Thurston, Jacob Zenn, and other scholars who have closely studied the microhistory of the evolution of Boko Haram based on a careful examination of a wide range of primary sources have previously discussed some of the issues in David’s article. In the 2020 article “Entangled Incidents: Nigeria in the Global War on Terror (1994–2009)”, Andrea Brigaglia and Alessio Lochi provided an extensive analysis of the 27 September 2006 letter Aminu B. Wali (then the Permanent Representative of Nigeria to the United Nations) wrote to the Chairman of the Counter-Terrorism Committee. In his book Unmasking Boko Haram, Jacob Zenn also discussed the transnational engagements between the Izala-scholar Mallam Yakubu Katsina and the Algerian-based GSPC and GIA.

These uncomfortable, traceable, verifiable, and evidence-based facts are known and documented even though many prefer to listen only to the set of narratives that suit their sectarian leanings. Shying away from confronting difficult conversations about your archive is an act of cowardice. It is only a matter of time; sooner or later, people would dig deep inside those records and ask uncomfortable questions that would put you on the defensive. It would help if clerics, rulers, and people with shady past address, reckon, redress, repair, and grapple with complicated, violent, and disavowed aspects of collective histories before academics, journalists, and curators of archive unearth their records for public scrutiny.

What is new in David’s article is the record and detailed information he unearthed that linked the identities of previously unknown actors to the web of Boko Haram’s history. At a time when the Attorney General of the Federation, Abubakar Malami, has defended the decision of the government not to name financiers who have been indicted for funding Boko Haram, David’s piece would certainly provoke questions. However, despite the trove of records in David’s article, he ended with a dangerous and conspiratorial conclusion by attempting to lump different issues together, including early al-Qaeda connections, the emergence of Boko Haram, and farmers/nomadic herders conflict.

Before addressing this conspiratorial bent, it is important to ask questions about the state-funded NGO in Jordan. According to the article, David hatched a narrative that incriminates the Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre (an affiliate of the Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought) as part of a coordinated international campaign with the intentional aim of distorting the reality of Muslim-Christian religious tensions and crisis in Nigeria. Yakubu Musa is the “black face clerical surrogate” whom the Jordanian NGO conferred the “500 Most Influential Muslims” badge to reward his role in this grand coordinated campaign. This narrative is consistent with the commentaries that often strip away the agency of African Muslims by presenting them as proxies and local clients doing the bidding, nefarious foreign plots, and the global expansionist agenda of Middle Eastern hegemons on the ground in Africa.

The Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought is the Jordanian version of the UAE-funded Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies (led by Shaykh Abdullah Bin Bayyah), the Qatari-funded Al-Qaradawi Center for Islamic Moderation and Renewal (led by Shaykh Yusuf Qaradawi), and the Moroccan-funded Higher Council Mohammed VI Foundation of African Oulema (led by King Mohammed VI and Ahmed Toufiq, the Moroccan Minister of Religious Endowments and Islamic Affairs). Arab rulers established these institutions to promote their soft power and competing state brands and foreign policies in Muslim societies across the globe. The Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought is particularly anti-Salafi in its religious orientation. The anti-Salafi leaning of this institution is evident in their 2007 launch of the inter-religious initiative “A Common Word” and their 2005 conference of Islamic scholars where they produced the “Three Points of Amman Message.”

The annual 500 most influential Muslims published by the Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought is an effort to promote mostly Sufi scholars. They mention the leaders of some mass Salafi movements only for political correctness. This political correctness is the reason Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute refers to Yakubu Musa as a leader of an activist Sufi brotherhood. Izala is not a Sufi movement. This begs the question, what exactly does the Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought seek to gain by forming a partnership with a Nigerian Salafi cleric to obfuscate the reality of Muslim-Christian tensions in Nigeria? David’s claim on the Jordanian connection does not add up.

David also seems to conflate the two Yakubu from Katsina. Yakubu Hassan Musa Kafanchan of Izala is different from Yakubu Yahaya of the Shiites Islamic Movement of Nigeria. The former earned his moniker “Kafanchan” during the 1987 Kafanchan crisis while the latter acted as the deputy of Ibrahim Zakzaky. Newsweek documented his face-off with Governor Yahaya Madaki in Katsina in the aftermath of the 27 March 1991 burning of the Katsina office of Daily Times. Like most religious clerics in northern Nigeria, the two Yakubu have drifted away from the anti-state proselytism they propagated in the past.

David’s article also attempted to frame the 2012 publication ‘Report on the Inter-Religious Tensions and Crisis in Nigeria’ published by the Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought and their recommendation of “grazing routes” as evidence of their alleged pre-emptive knowledge of violence related to nomadic cattle herding. In the article, David concluded with the paragraph:

“Very tellingly, at a time when conversations about violence related to nomadic cattle herding were not yet present in Nigeria’s political equation, a Jordanian organization with links to Yakubu Katsina — a known Nigerian terrorist — was already recommending “grazing routes” as a solution for a problem that for the most part, did not actually exist yet. 9 years later, the question is…how did they know?”

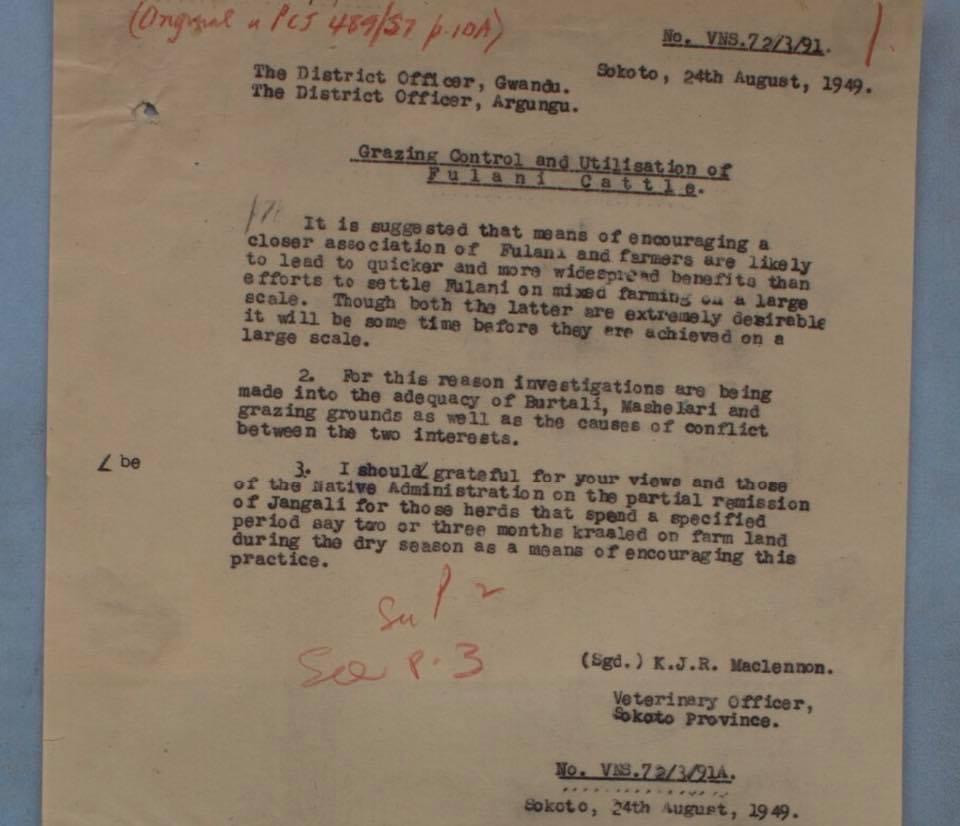

This conspiratorial conclusion contradicts the colonial and post-colonial history of nomadic herders and farmers’ conflict in Nigeria. The history of violence related to nomadic cattle-herding predates Nigeria’s independence. As early as 24 August 1949, the veterinary officer of Sokoto province, K.J.R. Maclennon, issued a memo under the title “Grazing Control and the Utilisation of Fulani Cattle.” In the memo, he wrote:

“It is suggested that means of encouraging a close association of Fulani and farmers are likely to lead to quicker and more widespread benefits than efforts to settle Fulani on mixed farming on a large scale.

For this reason, investigations are being made into the adequacy of Burtali, Mashelari, and grazing grounds, as well as the causes of conflict between the two interests.

I should grateful for your views and those of the native administration on the partial remission of Jangali for those herds that spend a specified period, say two or three months krasled on farmland during the dry season as a means of encouraging the practice.”

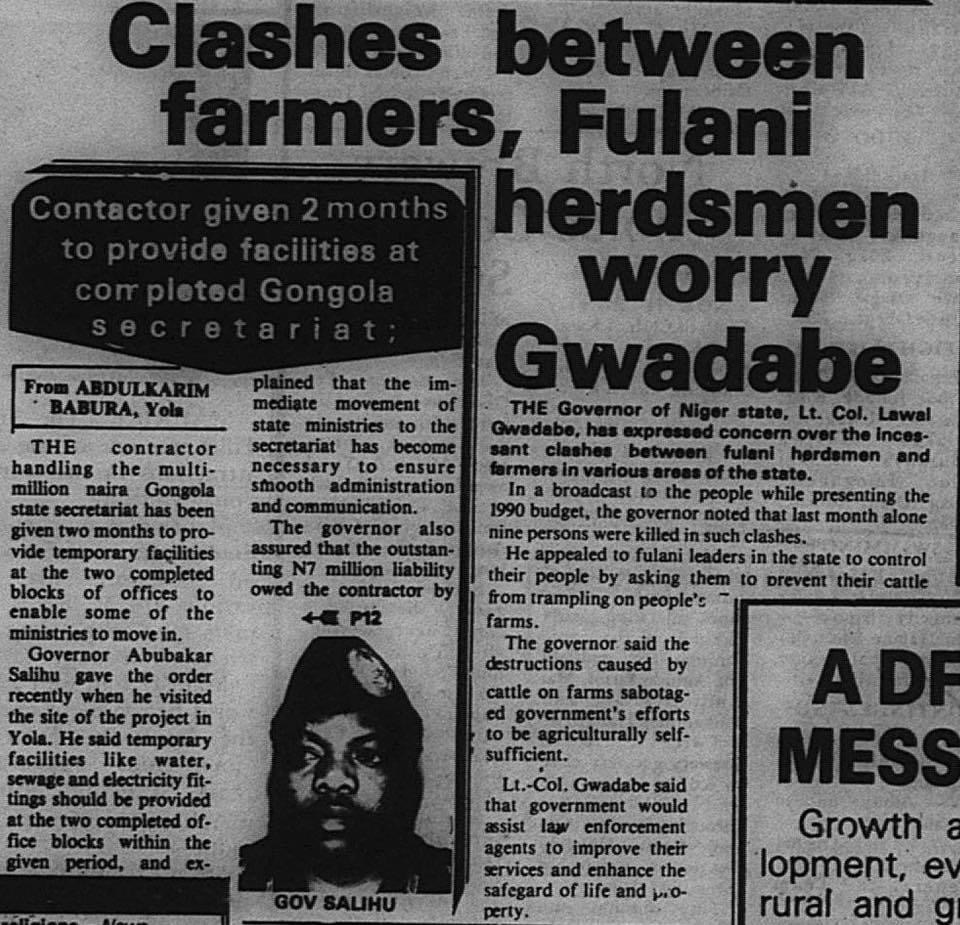

One out of the cache of evidence of the history of farmers and Fulani herdsmen conflict in the post-colonial period is the 1990 budget broadcast of the Military Governor of Niger State, Lt. Colonel Lawal Gwadabe, reported by Triumph Newspaper on 15 January 1990. In the broadcast, Lawal Gwadabe appealed to the Fulani leaders in Niger state to control their people by cautioning them against using their cattle to trample on people’s farms.

David is outrightly wrong to have concluded that conversations about violence related to nomadic cattle herding were nonexistent in Nigeria’s political equation when the Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought published its 2012 report. On the contrary, the colonial archive documented the “grazing routes” almost a century before the Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought issued their recommendation, which David attempted to present from a conspiratorial position.

So the answer to the concluding question of the article “9 years later, how did they know” is entirely conspiratorial and out of place. Historians should always endeavor to demystify the “perceived newness” often attributed to the present’s chaos and ruptures. Although this article is well-researched, it was severely marred the moment the author attempted to draw unfounded and conspiratorial conclusions.

N.B: For the sake of clarity, this piece is NOT a rejoinder to Hundeyin’s article. His article is thorough, well-researched and flooded with a trove of verifiable and traceable records. The only drawback in the article is the author’s conspiratorial conclusion and attempt to muddle unrelated conflicts together.

Kassim is a doctoral researcher at Rice University, USA.